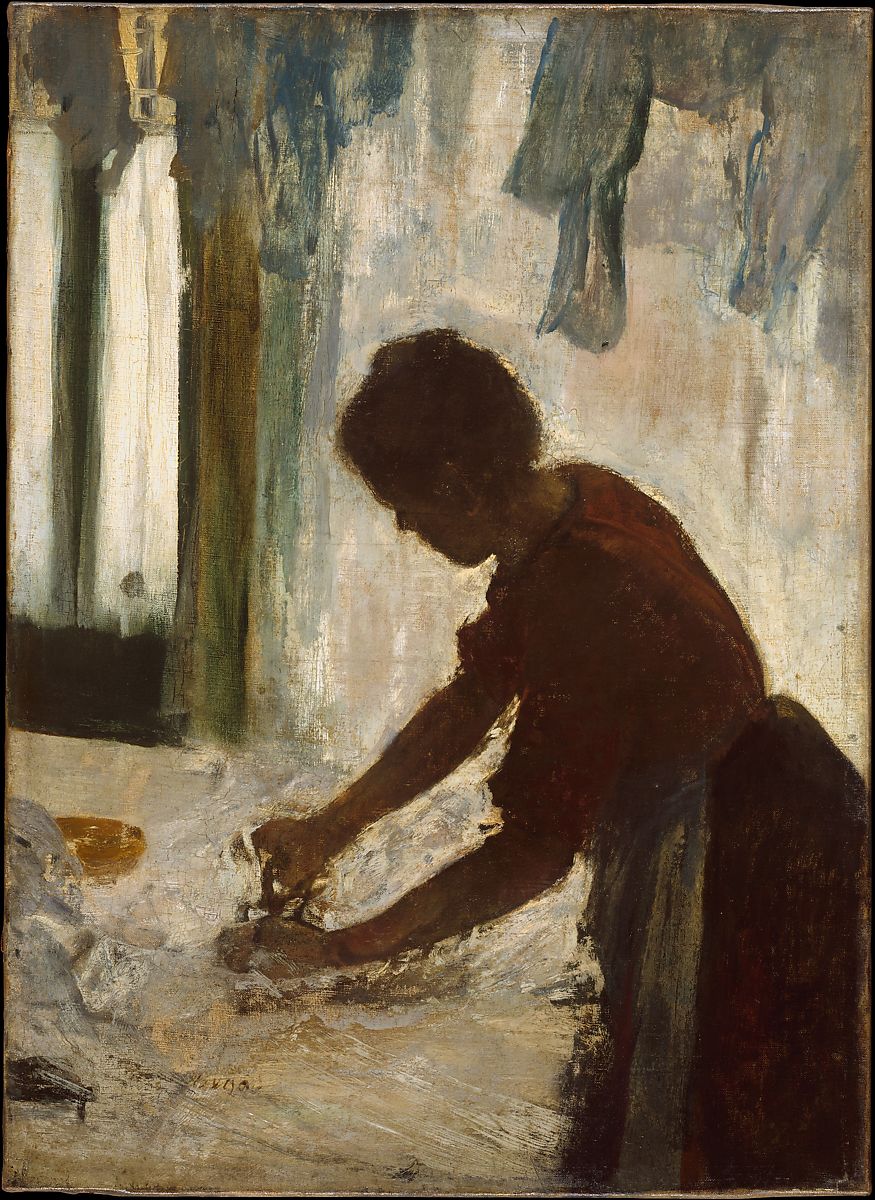

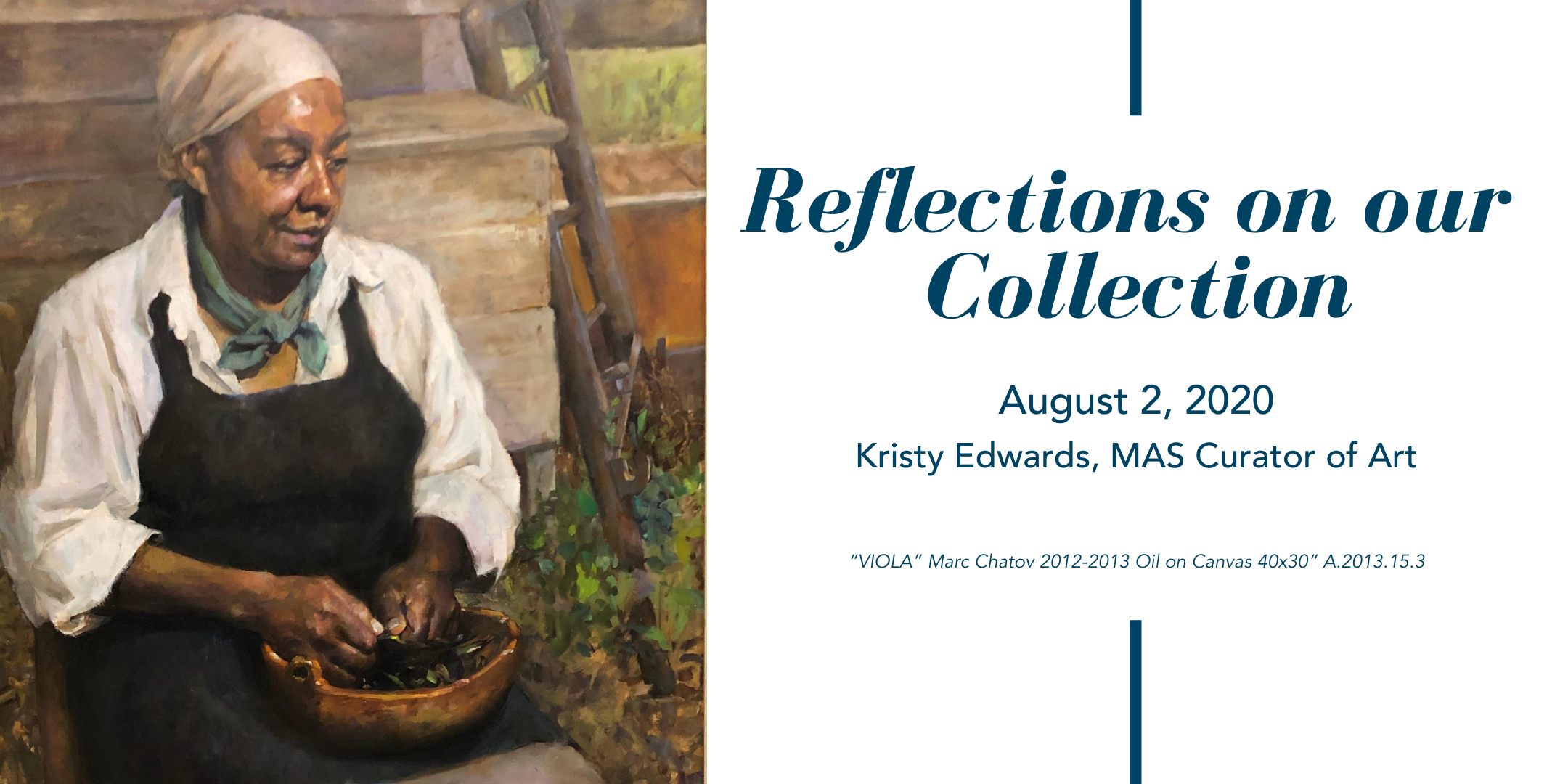

This week’s piece I chose from our permanent collection is this skillful and evocative painting of a woman lost in her thoughts while she performs a perfunctory kitchen task; shelling peas. Our painting “Viola” is one of a group of three that were gifted by the artist, Marc Chatov, from his private collection of art. The three pieces included one from his father, Roman, one from his uncle, Constantin, and this one painted by him. At first glance, you are taken by the slow-paced almost static scene of a quiet and simple moment of a woman at a task that did not require her full attention but allowed her to look off wistfully and remember or think of something else. Degas was known for capturing women engaged at everyday tasks such as grooming or homemaking as you can see here :

But I’d like to take you out of the subject matter for a moment. I’d like you to see into the skill that is present in the brushwork and artistic technical choices. I want you to see beyond what you might obviously see.

Marc studied art, got his necessary degrees and credentials from Georgia State University, but even more than that, he got his extra gifts from being raised at the easel by his father and uncle–both born in Russia at the dawn of the 20th century. He was steeped in art from his earliest days. His father and uncle taught Atlantans (and other Georgians) how to paint for many years at their atelier studio in Atlanta which they started in 1959. After they passed away, Marc inherited their atelier and its clientele and took it to another level. As he continued to share his expertise, techniques, and lessons of his forebears, he himself never quit learning. He had the degrees and the work but did not stop and rest on his laurels. He continued to enrich his art by following his desire for mastery and delved into his curiosity. His post-graduate teachers include the late Nelson Shanks. His other influences and friends include Albert Handell and Burton Silverman.

It might be intellectually obvious and correct for me to jump to the conclusion that Marc’s work has its roots in the style of Russian Impressionism/Russian Realism since his father immigrated from Russia in the 1920s. ( You can read about his father from a previous blog post) If you look at masters like Valentin Serov and Nicholai Fechin, you will see the connection.

But what I also see is his “style” might also have a tap root to the works of artists from La Belle Epoch, a period of time at the end of the 19th century turning into the early 20th century. Life after the Civil War was steady and prosperous and the wealth of Americans especially fostered this gleaming beautiful world of portraiture and painting of people in high society but also of all walks of life. Art in general was flourishing. Some of the artists who painted during this era were Americans John Singer Sargent, Cecelia Beaux, and Thomas Eakins, Swede Anders Zorn, and Spaniard Joaquin Sorolla. These artists were interested in painting in realism–capturing what they witnessed before their eyes- and not in abstraction which was dawning at the same time.

Masterful realism of this type includes something regular people might not know about regarding technique. Trained artists know how to employ technical devices that allow space for interpretation; for mood along with depicting the subject realistically. In Viola, Marc does not spell every single detail out like say Norman Rockwell or artists who went on to paint in photo or hyper-realism. This realism leans back and shakes hands with French Impressionism and the Post Impressionists. This era is a time right before things begin to get abstracted in the movements of Cubism and Abstract Expressionism as in the work of Russian painter Chaim Soutine, and Spanish painters, Picasso, and Joan Miró.

Let’s take a look at more of Marc’s technique. First of note, please look at the composition of this piece. Viola is depicted on the “X” of the canvas in a three-quarter turn meaning you get to see a slice of the receding side of her face. This is a classic portrait composition. However, this piece is not particularly a portrait. It transcends being just a painting of a particular human being named Viola. The painting becomes any and all woman shelling peas or peeling potatoes, or stringing beans by seating her squarely in the frame so that we are her. She is here before us and we can’t miss her. This is where we begin to try to relate to her.

After you’ve noted the placement of the figure, please notice the choice to make things in the background be slightly not as sharp or important as what he wants us to focus on–the main subject. Our eyes naturally only see sharply what we focus on; a painter must make that happen by obscuring and softening any part of the painting that is not most important. A device by which he might do this is to employ “lost edges” or “transparent shadow”. These two technical artistic devices are much like a rest in music or certain punctuation in poetry. There is mystery in silence and darkness–what is left unsaid. It is in the shadows we must look for clues, it is in the nuanced line lost between what we see and can’t see that draws us close. There are hundreds if not thousands of choices an artist must make to pull off a painting like our Viola.

Marc’s brushwork alternates between being highly finished and loose and evocative. When an artist leaves his strokes visible but not distractingly so, he allows us to meet him. He is present in the painting. Those strokes are evidence that he is on the other end of the brush. And in him are all his impressions, emotions, thought- subconscious and conscious-, his skill, his attitude toward life, the subject, his passion for art, painting.

The story of Viola is worth telling you. Marc is a game hunter and during a hunt years ago, he came across a small graveyard in Southeast Georgia and was moved by the gravestone which was hand carved with the simple name “VIOLA”. Since the land had had sharecroppers living there and also had been a plantation during slavery, Marc tried to imagine who she might have been. She hauntingly reached out to his imagination, calling him to paint her in his mind’s eye. This is the result of that communication between the possible spirit of someone in the past and an artist with a honed inner ear.

Marc pointed out recently something we might not discover about Viola on our own. By sharing his thoughts and intentions of this painting, we are able to know more; see more. He told me in our conversation on Instagram Live, that there is a dichotomy in mood to be found between her face and her hands. The hands show a tenseness and clenching while her countenance shows a more poised and placid mood. Marc is often interested in the deep psychology of people and he realized that this might be a way to show us that we can’t make assumptions about what a person might be experiencing by their face, which might be well trained to hide the deeper emotions. By sharp detail, he brings our eye to the hands which don’t know how to lie or to pretend. The truth they tell is of the anxiety and tension of being a sharecropper or enslaved.

We are in the presence of a magnificent piece of art when we stand in front of Viola. Nearly life-sized, she sits quietly as evidence of a life of a woman of her time and place of life. She sits as an example, also, as artistic mastery and nod towards one of the most beautiful painting eras of the history of painting - the turn of the 20th century. The Chatov Family has made their mark on the world through their art and we are a better world for it.

Thank you for looking at Viola with me. And thank you to Marc Chatov for listening to her call from the aether to be reimagined, recalled, and painted to be remembered for the ages.

My best,

Kristy Edwards, Your Curator of Art MAS